The records of the Continental Congress confirm that the need for a declaration of independence was intimately linked with the demands of international relations. Without a declaration, Paine concluded, "he custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until, by an independence, we take rank with other nations" (2). Foreign courts needed to have American grievances laid before them persuasively in a "manifesto" which could also reassure them that the Americans would be reliable trading partners. In particular, France and Spain could not be expected to aid those they considered rebels against another monarch. In February 1776, Paine argued in the closing pages of the first edition of Common Sense that the "custom of nations" demanded a declaration of American independence, if any European power were even to mediate a peace between the Americans and Great Britain. Thomas Paine's bestselling pamphlet, Common Sense, made this motivation clear.

To transform themselves from outlaws into legitimate belligerents, the colonists needed international recognition for their cause and foreign allies to support it.

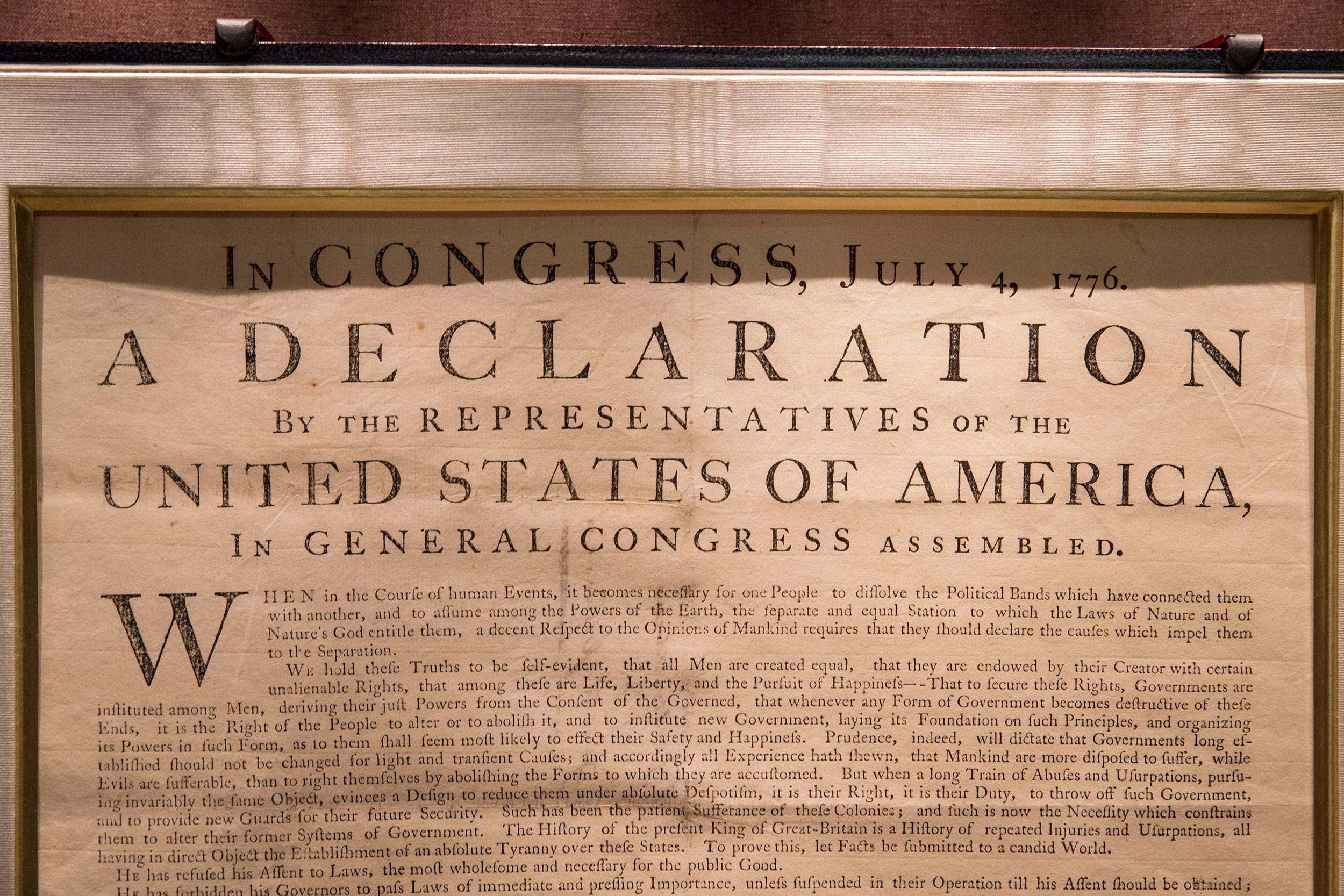

In August 1775, George III had already turned the American colonists into rebels by declaring them outside his protection. Its primary intention was to turn a civil war among Britons, and within the British Empire, into a legitimate war between states under the law of nations. The Declaration of Independence was therefore a declaration of interdependence. With that concluding statement, the United States announced that it had left the transnational community of the British Empire to join instead the international community of sovereign states.

WHO WAS THE MAIN AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE FULL

The United States intended to join them on an equal footing "as Free and Independent States" that "have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which independent States may of right do" (1). As the opening paragraph stated, the representatives of the states were laying before "the opinions of mankind" the reasons "one people" had chosen "to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them." Those "powers of the earth"-meaning other sovereign states-were the immediate international audience for the Declaration. The very term, "United States of America," had not been used publicly before its appearance in the Declaration. To ask just what the Declaration declared is to see that, first and foremost, it announced the entry of the United States into international history. It will then conclude with some reflections on what the Declaration's afterlife can tell us about the broader modern history of rights, both individual and collective.

This can be done for the Declaration in a number of ways: by showing that it was the product of a pressing international context in 1776 by examining the host of imitations it spawned and the many analogous documents that have been issued from 1790 to 1988 and by comparing the starkly different histories of its present reception within and beyond the United States.Īccordingly, this essay will deal with the immediate motivations that led to the Declaration in 1776, with the first 50 years of reactions to it, at home and abroad, and with the subsequent history of declaring independence across the world from Venezuela to New Zealand. If a document so indelibly American as the Declaration of Independence can be put successfully into a world context, then surely almost any subject in United States history can be internationalized. Little wonder, then, that it stands as a cornerstone of Americans' sense of their own uniqueness. The "self-evident truths" it proclaimed to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" have guaranteed it a sacrosanct place as "American scripture," a testament to the special qualities of a chosen people. Where better to begin internationalizing the history of the United States than at the beginning, with the Declaration of Independence? No document is as familiar to students or so deeply entwined with what it means to be an American.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)